Smart Thinking

Ideas Come in Speaking

In one of my master’s research seminars, I was told about a paper, On the gradual construction of thoughts during speech, written by German author Heinrich von Kleist (1771-1811). In the paper, von Kleist advises that,

If there is something you want to know and cannot discover by meditation, then, my dear, ingenious friend, I advise you to discuss it with the first acquaintance whom you happen to meet. He need not have a sharp intellect, nor do I mean that you should question him on the subject. No! Rather you yourself should begin by telling it all to him.”

Early in conversations with friends, I sometimes raise philosophical problems that I have tackled in essays, or I talk about problems that I have recently come across in a book and found deep or surprising. On such occasions, they are topics that I do not fully understand. Yet, generally, conversations are thought to proceed on the basis of what one understands; that is, one should speak about what one already knows. This way, one is able to perform some kind of service to others; to inform or enlighten others. But von Kleist thinks we should first and foremost be concerned with enlightening ourselves. He says:

I want you to speak with the reasonable purpose of enlightening yourself, and it is possible that each of these rules of conduct, different as they are, will apply in certain cases. The French say: l’appétit vient en mangeant [“appetite comes with eating”] and this maxim holds true when parodied into: l’idée vient en parlant.

The parodied maxim is that ideas come in speaking. Just as writing can lead to a synthesis of new thoughts and make old ones clearer, the same can be said of thought spoken out loud.

Seeing the Bigger picture

There’s a parable about the building of a cathedral.

A man walks up to a stone mason and asks, “what are you doing?”. The mason replies, “I’m shaping stones”. The man then walks up to a sculptor and asks the same question. The sculptor replies, “I’m making a gargoyle”. Finally, the man walks up to a floor sweeper and asks, “what are you doing?”. The floor sweeper replies, “I’m helping to build a cathedral”.

A question to keep in mind is, how does this thing that I’m studying or working on fit into the bigger picture?

I saw an excellent demonstration of keeping the bigger picture in mind at my alma mater, which has the motto “to understand the causes of things”. At the beginning of each lecture, the professor would connect that week’s topic to the broader topic the course was concerned with. In a cognitive science lecture, a topic on some aspect of the mind would be connected to how that knowledge could help improve our lives, or form sensible social policy. Yet it’s rare to see the question posed outright.

It’s easy to get trapped in the details and lose sight of what’s important. In certain philosophy books or papers, an author might fill their text with archaic jargon, obscure symbols, or some dubious metaphysical analysis about possible worlds, and it’s clear getting into those passages that they’ve lost sight of the bigger picture. It’s no longer clear why that problem or question is being studied. But we’ve all been there.

Take neuroscience or cognitive science. They’re interesting fields in their own right, so it would be easy to get drawn into some minute issue. And there are interesting, important questions and problems to be solved, especially disorders of the brain and mind. Yet what’s important about those fields is the bigger picture: figuring out what we are, what a person is.

As the saying goes, however, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. There are problems or questions that should be pursued because they are inherently interesting or valuable. I have in mind questions related to hobbies, like, “how could I improve my painting skills?”, or “how could I improve my marinara?”.

Posing questions to ourselves about how things fit into the bigger picture, and why they’re important, helps us to transition from the micro-picture to the macro-picture. To see the forest for the trees.

It’s a question that helps us to step out of the fog.

The Three W’s of Memory

Memory is amazing; it’s the treasure house of our lives. As persons, we refer to memory not by neural processes, but experientially, through images and words. When we remember, it’s as if we lasso memories straight from the darkness and into the mind. As a physical process, “memory” refers to the activities in the brain which trace, store and retrieve information. Discovered some time ago, memory possesses this really interesting property sometimes referred to as the Three W’s, for “When”, “What”, and “Where”. Suppose I asked you, “where did you last go on holiday?”. And suppose you said, “Italy”. And just like a daisy chain, when one of the three W’s is triggered, the other two are automatically brought into the awareness of the mind, and the neural traces are subjectively experienced as a mental image or linguistic symbol.

So in addition to the spatial context of the place where your memory occurred, you’ll also recall the substantial context of the memory––what you did on your holiday––and also the temporal context––when you went on your holiday. There’s various complex interrelations at play given we remember whatever it is we’re paying attention to at any given time; for instance if it was a special period when you went on holiday, if it was a special place, or if you did something special. But the daisy chain of memory runs together. “What”, “When”, and “Where” go in tandem because it’s an extremely helpful and efficient way to pull information from the mind.

How to Read More Books

Read everyday.

Give yourself a target of how many pages you’re going to read. Whether it’s 10, 20 or 50 pages a day. It keeps you focused.

Read widely. Read two or more books at a time. Combining non-fiction and fiction books works really well. One will give you new knowledge, the other will fuel your imagination and spirit.

Often, ideas will mix in your mind without you even thinking about it. You will broaden your horizons and be more creative. You will develop a complex mind.

The time-tipping effect works well for reading more. If you are reading three books at a time, and you’re 70% through the first, 60% through the second, and 50% through the third, it might make sense to finish the first book. Repeat the process with the other two books, or bring in a new, third book. Then keep it going.

Reading often will make you a better reader. Over time you will be able to read more complex books. And longer, deeper books. Take your time reading the books you love. And read them again when you want to.

Give yourself time to reflect on what you’ve read. Books can contain important ideas, and reflection is key to making the most of those ideas.

Think about what you want to read next. Pick up a book you’re sure you want to read. Reading great books will leave you wanting more.

Listen to audiobooks. Listen and read along with matching editions of books. It’s an amazing experience.

Consider reading with a pen in your hand. You can mark the top corners of a page and star or run a vertical line next to paragraphs with important ideas. A flick of the pages will allow you to quickly get back to those ideas. Summarise ideas on the page in your own words.

New ideas will add depth to how you view and interact with the world. Reading will change your life. You’ll want to read more.

Always have a book on you.

Learning and Creativity

After 72 hours of learning something new, if not reinforced, your memory of the content will reduce by half.

After a week, it will have reduced by three-quarters.

Take notes. Go over them and reflect to strengthen your memory.

In all its types, memory is the gateway to the mind. The stronger your memory, the better your access to its contents will be.

Split your learning in two: ‘inside lessons’ and ‘outside lessons’. Inside lessons are ideas or insights that you have generated. Outside lessons are what you have learned from others.

Splitting lessons identifies trigger points for how your insights were generated. It’s a means of tracking the causal patterns of ideas.

Cluster your ideas together. With clusters, you can see which interconnected ideas stand out, and what’s taken your interest.

Our minds are pattern makers/identifiers. Sometimes you will see a connection between ideas, and sometimes you won’t. Be persistent.

Follow your instincts. Don’t let doubt or the chatter in your mind get in the way if an idea feels right. Sometimes ideas will show you the right trajectory to take in your creative work.

Get the gist of whatever it is you’re learning. Keep it simple. Restrict ideas to their essence.

The Big Ideas

Take the best big ideas from a variety of disciplines.

Learn to bridge jurisdictions.

Taking the big ideas from philosophy, the natural sciences, psychology, engineering, or computer science, means that you can see the operations of the world from an emergent vantage point; how processes come together, and how they cohere, into making the phenomena that fill reality.

One of the advantages in big idea thinking is getting to the bottom of what constitutes reality.

It is a way of reasoning from first principles; to think bottom up. It is to think about what you know is fundamentally true –– the first principles –– to new and sound conclusions or solutions.

First principles are like the building blocks which one’s conclusions rest upon. So ask: “What am I sure of that’s true?” and then reason from there.

We know the world is made of atoms, which make molecules, and which make organisms and the objects of reality. Ask yourself: how else could atoms be put together to make something that could be of value?

The natural world is the ultimate engineer. It has fashioned galaxies, stars, planets, organisms, and inanimate matter. How could we use the fundamental principles of reality to get to the root of causes and to solutions that are of value to us?

Frames for Decision Making

The Frame of Reference

Everything we experience is through a perspective––a frame of reference.

If you’re inside a moving train, your frame of reference is inside the train, as the train and the other objects inside the train appear at rest.

To someone outside the train, their frame of reference is at rest and the train is moving at speed. The speed of light is the only exception, since at the speed of light all frames of reference are constant. This is a principle of Einstein’s theory of special relativity.

In order to get a full understanding of an event or situation, look from a variety of different frames of reference. This way you can aim towards true objectivity of a given situation or problem.

Account for frames of reference when making decisions. The frame of reference of an observer is a first principle in physics. It is a fundamental axiom about how reality is constructed.

The Third Story

Force yourself to tap into a third story frame of reference to better understand people, their views and their motives. The third story is the frame of reference of an impartial observer.

To tap into the third story reference frame, imagine if the situation you’re attempting to understand or make a decision on was being recorded or filmed. What would an outside audience say about the event? How much of your own view would they share or agree with?

If you can articulate others’ views, you’ll be more likely to make objective or well-considered decisions.

Asking Good Questions

“It is easier to judge the mind of a man by his question rather than his answer” - Pierre de Lévis

We’re all looking to establish a deep connection with other people. To know that we have friends in this here likely infinite cosmos. It’s true that we all want to be understood. Yet, we are often thwarted by our inability to pay proper attention to what others are saying. Sometimes we fail to read the room. Given that words are but faint symbols for our ideas, feelings and experiences, words often lack the power to carry what we mean. Time and time again, in conversation, we impose judgments and preconceptions onto the words of others. Generally, and I think this is right, what we want from others is something that’s a bit more mixed in nature. Here’s what I mean. We desire for others to understand us, to have compassion, and to hear our point of view. At the same time we also want to preserve our agency and independence. To be precise, we wish to avoid others completely imposing their way of life onto us. Not to make their attitudes our own, or to change how we view the world against our wishes. We don’t want to be blasted with stimuli; to have a constant viewpoint cast upon us that bears little relevance to how we feel or what we think in a given moment. No doubt, then, having good conversation or establishing deep connections is hard work.

I’ve given a lot of thought to the quote by de Lévis, which is often misattributed to Voltaire, that we ought to judge someone by their questions rather than their answers. But what the hell is a question, anyway? Broadly speaking, a question is an utterance that fulfils the function of a proposition or an illocutionary act, a request for information. To some degree, questions also play the vital role of social connection. When we enjoy someone’s company, we tend to ask them questions. Second, what makes for a good question? In the context of conversation, I think a good question is one that’s enjoyable or interesting to answer. In other words, good questions provide the opportunity for enjoyment or delight. Good questions keep us interested and focused. They can be a stable bridge for creating deep, lasting connections with other people.

Let me say something about why we’re sometimes left wanting in conversation and why we hold back. The first reason that comes to mind is that we don’t know what questions other people want us to ask. For fear of coming across as inept or pushy, we refrain ourselves. Second, we are self-absorbed and want to impress or prove our own cleverness. But I think the most compelling reason why people don’t ask good questions is that it just doesn’t occur to them. People don’t realise the value good questions play in creating enjoyable dialogue. Imagine how Plato’s dialogues would have turned out if Socrates was useless at asking questions.

So, besides, how do we ask a good question? We can first ask more questions. But in a manner that’s not presupposing or leading. We could frame questions in a neutral, relaxed and open-ended manner. Questions of the sort that begin with “what?”, “how?”, “why?”, “when?”. In effect, follow-up questions. They’ll help to move dialogue forward. Specific, closed questions might also be used, but perhaps sparingly. What we ought to avoid is questions that stall dialogue. Take for example those occasions when we act in disingenuous ways. We have a feeling inside us that doesn’t quite feel right. Sometimes we ask a question for the sake of it. For continuing a conversation that we’re too invested in. Notice when it occurs and re-align yourself. You’ll feel right when you ask questions that you value. Questions that you find interesting and want to hear the answer to. Let me reiterate: good questions matter. They can be the difference between learning something mundane or something extraordinary. As well, at times, it might just be okay to ask, “what question do you want me to ask you that I’m not asking?”. Lastly, it will help to avoid interruptions or being afraid to just sit still for a minute in silence. Because who knows what you’re going to hear.

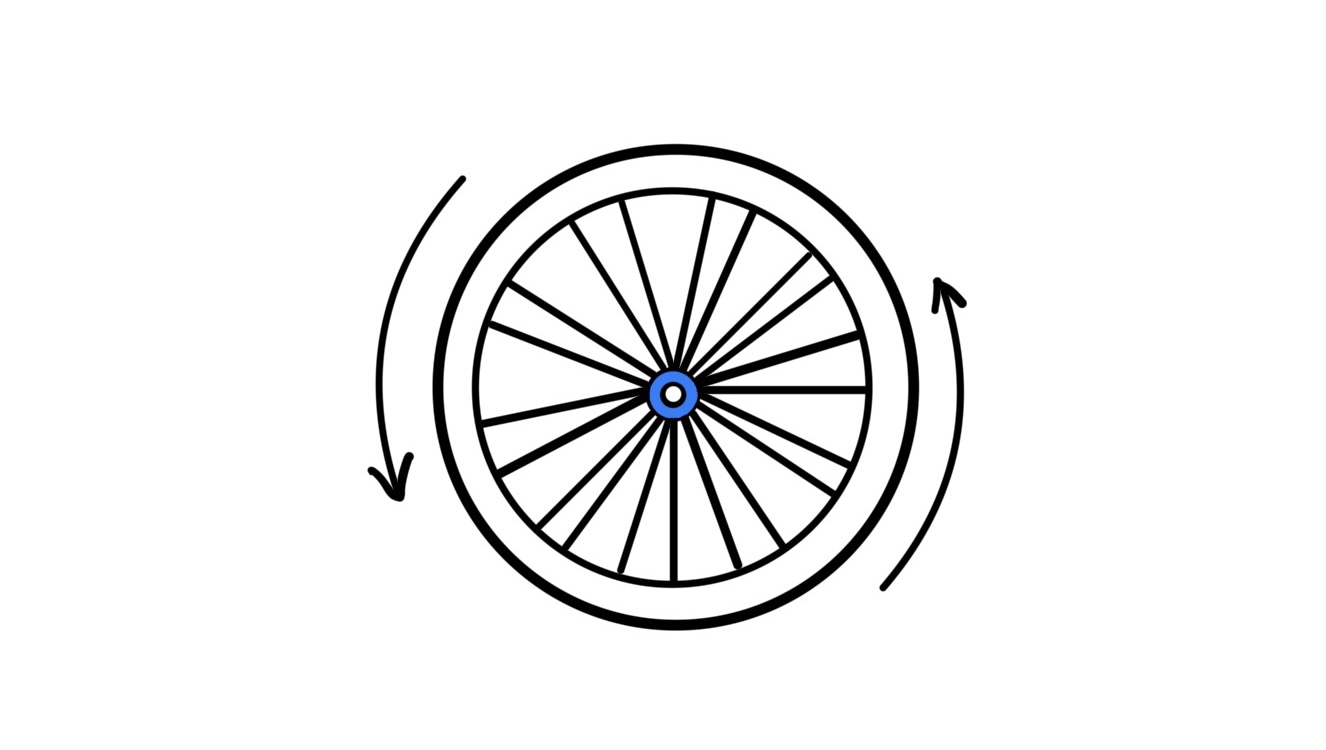

Spokes and Wheels Mental Model

In this post, I am going to illustrate and describe a new mental model. It is my own original contribution to the representational world of mental models. It is the Wheels, Hubs and Spokes model. It is a framework for reasoning. The aim of the model is to serve as a symbolic container for three particular and unique things: a central question, idea or phenomena to be explained (the explanandum), the explanation (the explanans) and the momentum of rotation to keep us from straying away from the phenomena we wish to explain. The model is in the form of a bicycle wheel and contains a rim, hub and spokes.

Here’s how it works. We begin with the hub, which represents a phenomena or central idea we wish to understand. This can be anything we wish it to be: a natural or physical phenomena, a concept, an idea, or a question. Then we add a rim. The capacity of the rim to rotate represents the notion that we wish to ‘circle’ some phenomena so that we can understand it. For instance, let’s say we wish to explain Aristotle’s concept of potentiality. We place the phenomena of ‘potentiality’ into the hub. Once we have identified the first constituent concept or explanation sentence, it will make up our first spoke. The spoke is then placed into the hub and connected to the rim. Let’s take Aristotle’s concept of the four fundamental causes and link them to the hub. They are the material cause, the efficient cause, the formal cause and the final cause.

The material cause relates to the constitutive material that something is made of; for instance the tissue and blood that constitutes our bodies. Our efficient cause is our parents; who made us. The efficient cause of a statue, for instance, is the sculptor who has chiselled the stone into shape. The formal cause relates to the form, arrangement or shape of something; in our case, it is the way we look. Our DNA determines our constitution and the way we look; our general features such as the possession of a head and face, torso, arms and legs and our specific features that constitute our own individuality. The final cause refers to the telos, the reason or purpose for the existence of something. For Aristotle, potentiality is linked to the final cause. The final cause is the only cause within our control. We have the potential to breathe, to grow, and to walk. Animals and plants also fulfil some of those potentials. But humans also have rational potentiality, which is a special type of potential intrinsically linked to conscious thought that is within our control. And so, in this sense, we have the power or ‘dynamis’ to bring about or do something that fulfils our underlying rational potential in the form of talents, goals or specialist action (say scientific research). By realising our potential — by first being conscious of and then making real — we can walk on the road towards achieving eudaimonia, or happiness.

Now that we have identified the phenomena we wish to explain (potential), some of the constitutive explanation concepts or sentences (e.g the four fundamental causes), we can add more explanatory concepts in the form of spokes to the hub. We can add concepts like delayed impact of form, reasoning, training, intention, DNA or telos. Each concept is independent or a self contained unit. If a concept doesn’t fit well in the overall explanation, we can replace it. The model becomes complete when we take into account the angular momentum of rotation: we use the rotation of the model to represent the idea that we are to always circle the main topic. The rotation around the hub helps us keep focus. You can make as many different models as you see fit. So what is the telos, or purpose, of the model? Its purpose, like other mental models, is to represent in thought how something works and to help us solve complex problems.