Circle of Competence

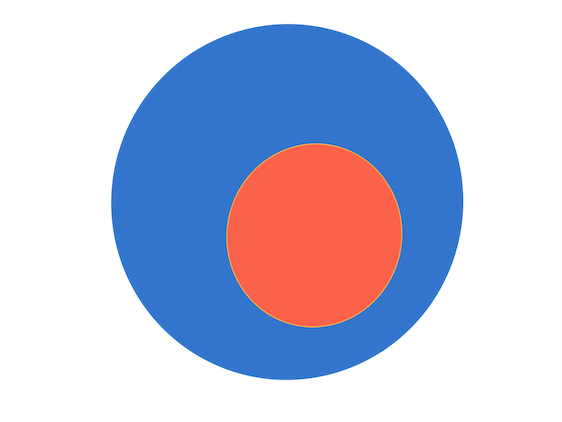

In the above diagram, the Red Orange shaded area might represent one’s so-called “circle of competence”. Think of this as the area which represents the stuff that you know. The idea is that, through experience and study over time, one has gained valuable knowledge about some parts of the world. Conversely, the Blue area might represent stuff that you believe or think you know, but actually do not. Let’s call this the Circle of Incompetence. It is the misattribution of knowledge possession onto ourselves, possibly a by-product of the Dunning-Kruger effect. The stuff outside the shaded areas represents everything-else.

As a concept, the origin of the circle of competence can be traced to Andrew Carnegie. In its modern form, it was developed by Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger, respectively the chairman and vice-chairman of the American conglomerate Berkshire Hathaway. In 1994, Munger gave a speech titled “A lesson on elementary, worldly wisdom as it relates to investment management and business” at the University of Southern California Business School where he draws up on the model. In the speech, Munger explains:

“You have to figure out what your own aptitudes are. If you play games where other people have the aptitudes and you don’t, you’re going to lose. And that’s as close to certain as any prediction that you can make. You have to figure out where you’ve got an edge. And you’ve got to play within your own circle of competence.”

In order to get ahead in life, Munger’s advice is to operate inside the circle of competence while simultaneously working to expand it. This now brings me to my next question: how should one expand one’s circle?

First it is important to say something about the problem of unknown unknowns, the things we don’t know that we don’t know. One can reasonably assume that everything in the space of everything-else is an unknown unknown. So how might we expand the circle so as to transform unknown unknowns into known unknowns (circle of incompetence) and eventually into known knowns (circle of competence)?

Biographer James Gleick outlines in his book, Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman, that Feynman used to keep a ‘Notebook of Things I Don’t Know About’. Gleick says:

“Feynman had not yet finished his second year of graduate school. He remained ignorant of the basic literature and unwilling even to read through the papers of Dirac or Bohr. This was now deliberate. In preparing for his oral qualifying examination, a rite of passage for every graduate student, he chose not to study the outlines of known physics. Instead he went up to MIT, where he could be alone, and opened a fresh notebook. On the title page he wrote: Notebook Of Things I Don’t Know About. For the first but not the last time he reorganized his knowledge. He worked for weeks at disassembling each branch of physics, oiling the parts, and putting them back together, looking all the while for the raw edges and inconsistencies. He tried to find the essential kernels of each subject. When he was done he had a notebook of which he was especially proud.”

In order to expand our circle of competence, our aim, then, is to first restrict everything-else into the finite concrete areas that we care to learn about. We have to identify what kind of classifications exist. Fortunately for us, the ancient people of Egypt and Mesopotamia, Aristotle, and the great scientists that have followed since then have already done most of the heavy lifting, to paraphrase Plato, in carving nature at its joints in order to produce the branches of science. Let’s say classical mechanics—the relationships between force, matter and motion—is the thing that we don’t know about. We can begin by initially scoping out the subject area, say by finding a first year university syllabus on the topic, and then drawing from the recommended book(s). We might then try to understand and summarily breakdown what Feynman called the “essential kernels” of the topic—the fundamental concepts, such as acceleration, angular momentum, and so on. With time, patience and effort, classical mechanics will then be enveloped by our circle of competence. At that point it becomes something that we know that we know.